On August 27 it will be sixty years since the death of Le Corbusier. He remains one of the most influential and controversial figures in modern architecture. Some of his political views are debated yet his work continues to inspire. At the heart of his legacy stands the Modulor, a system that tried to unite the human body, mathematics and architecture into harmony.

Tracing the Steps of Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier was born Charles Édouard Jeanneret in 1887 in La Chaux de Fonds Switzerland. In his early years he studied decorative arts and watchmaking design before turning fully toward architecture. His curiosity and drive for knowledge soon took him beyond his hometown. He traveled across Europe and the Mediterranean studying classical monuments and vernacular buildings that deeply influenced his later theories. Journeys to Italy, Greece and the Near East helped him develop an eye for proportion geometry and the relationship between human life and space.

During these travels he also connected with leading figures of modern architecture. He met Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius who would later define the Bauhaus movement in Germany. Although Le Corbusier was never a member of Bauhaus his ideas ran parallel to theirs. Both sought to unify art craft and technology in service of modern living yet he always pursued his own independent path.

Over the decades his writings, manifestos and architectural projects made him a central voice in shaping twentieth century design. His life came to a close on August 27 1965 when he passed away while swimming in the Mediterranean Sea. Sixty years later his legacy continues to spark admiration, debate and reflection.

Works and Principles

Le Corbusier did not just design buildings he created an entire philosophy of how modern life could be housed and organized. His most famous contribution was the Five Points of Architecture which called for buildings raised on slender columns, open interiors, horizontal windows, free facades and flat roofs turned into gardens. He brought these ideas to life in projects that became icons of modernism. Villa Savoye near Paris is perhaps the clearest demonstration with its lifted structure and ribbon windows, while the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille introduced a bold new vision of collective housing. On an even larger scale his plan for Chandigarh in India showed how these principles could shape an entire city.

Beyond architecture he was also a painter, a sculptor and a furniture designer. His paintings often explored abstract forms and bold colors while his collaborations in furniture design produced timeless pieces such as the LC series chairs and lounges. This artistic work was not separate from his architecture but part of a single vision where art and building complemented one another.

His writings such as Vers une Architecture further amplified this vision calling for simplicity and order while drawing inspiration from both classical monuments and modern machines. With these works he placed himself at the center of the modernist movement and helped define a new international style.

Le Corbusier Modulor

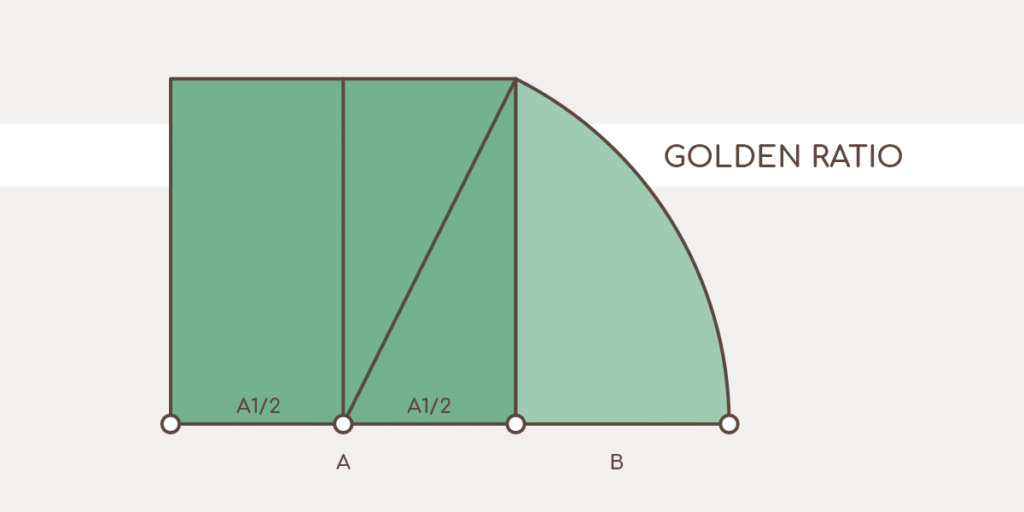

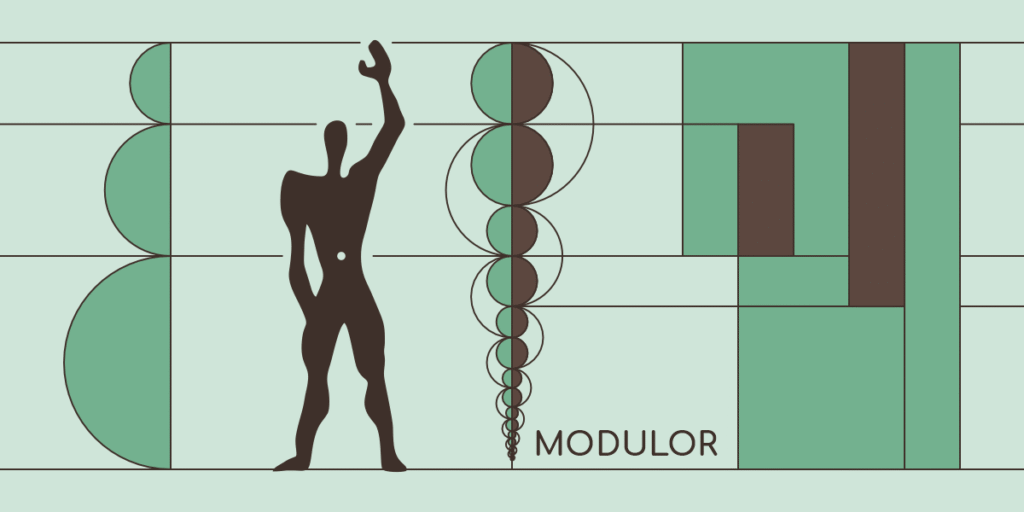

At the heart of Le Corbusier’s vision stood the Modulor. It was his attempt to create a universal system of proportion that could guide architecture and design toward harmony. Rather than relying only on abstract mathematics he rooted the system in the human body.

The Modulor began with a simple figure, a man standing tall with one arm raised. From this image Le Corbusier drew a set of measurements linked to the golden ratio, a mathematical relationship long admired for its balance and beauty. By combining the human scale with this timeless proportion he created a tool that could be applied to buildings, furniture, and even cities.

The Modulor was more than a ruler, it was a philosophy. It suggested that design should always begin with people, not with machines or pure function. Dimensions of doors, windows, staircases, and living rooms could all follow this rhythm, making spaces that felt natural and comfortable.

Le Corbusier tested the system in many of his works, most famously in the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille where corridors, apartments, and communal areas followed Modulor proportions. He believed this approach would bring order and coherence to the chaos of modern life. The Modulor also influenced his efforts to design affordable housing. The Maison Loucheur project was meant to create standardized homes for mass production, while the Cité Frugès in Pessac experimented with low cost worker housing. These projects showed both the promise and the limits of his vision. Costs often ran higher than expected, yet the ambition to connect human scale with industrial production marked an important step in modern housing design.

The reach of the Modulor extended beyond housing. Le Corbusier contributed to the design of the United Nations Headquarters in New York, and there too the proportions of the Modulor played a role. His eye for proportion and his use of perspective created spaces that felt larger, lighter, and more monumental than their raw dimensions suggested. Carefully framed views and subtle adjustments in scale gave his buildings both balance and drama.

Critics argued that the Modulor simplified the diversity of human bodies into a single abstract figure, yet its influence spread widely. Designers saw in it a bridge between art, science, and daily living. Even today the Modulor remains a powerful symbol of human centered design, reminding us that architecture is not only about structures but about the people who live within them.

From Modulor to Domovago

The Modulor was created to bring human proportion into the heart of architecture. That search remains just as relevant today. In a world where many people live in compact apartments or adapt to flexible spaces, proportion can make the difference between a room that feels cramped and one that feels balanced.

Applying the Modulor to small living spaces means paying attention to the rhythm of dimensions. The height of a ceiling, the width of a doorway, or the placement of a window can follow the harmony of human measure. Even a narrow corridor can feel generous if its proportions respect the body that moves through it. Storage, seating, and work areas can all benefit from these relationships, turning necessity into comfort.

Domovago carries this spirit forward. Just as Le Corbusier imagined a house as a machine for living in, Domovago seeks to create spaces where human scale and modern needs meet.

Sixty years after the death of Le Corbusier his ideas continue to shape the way we think about living. The Modulor stands as both a tool and a symbol, and in Domovago it finds new ground. A home designed with harmony in mind becomes more than shelter. It becomes a place to live fully.

Key Takeaways

- Le Corbusier’s Importance: A central figure of modern architecture whose ideas continue to shape how we see buildings and cities.

- Human at the Center: The Modulor placed the body and its proportions as the foundation of design.

- Legacy of Harmony: The Modulor lives on in Domovago where small spaces and modern needs follow the rhythm of human scale.

Credits

- Written by: DB

- Images: DB, Le Courbusier by Joop van Bilsen / Anefo / the Dutch National Archives, Villa Savoye by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra