Have you ever played with LEGO bricks and felt that balance between freedom and limitation? The pieces only connect in certain ways, yet within those boundaries entire cities, machines, and imaginary worlds take shape. This is the essence of modularity, a design principle where parts are made to work together, proving that limitations can become the very spark of creativity.

What is Modularity?

At its core, modularity means breaking something down into smaller, self-contained parts that can be combined in different ways. Each piece has its role, yet the real power lies in how they connect, adapt, and evolve as needs change. Modularity is not about complexity but about flexibility, creating systems that can grow without losing their order. It is why a set of simple components can build a house, why a kiosk can become a city corner, and why a handful of bricks can become a castle in a child’s hands.

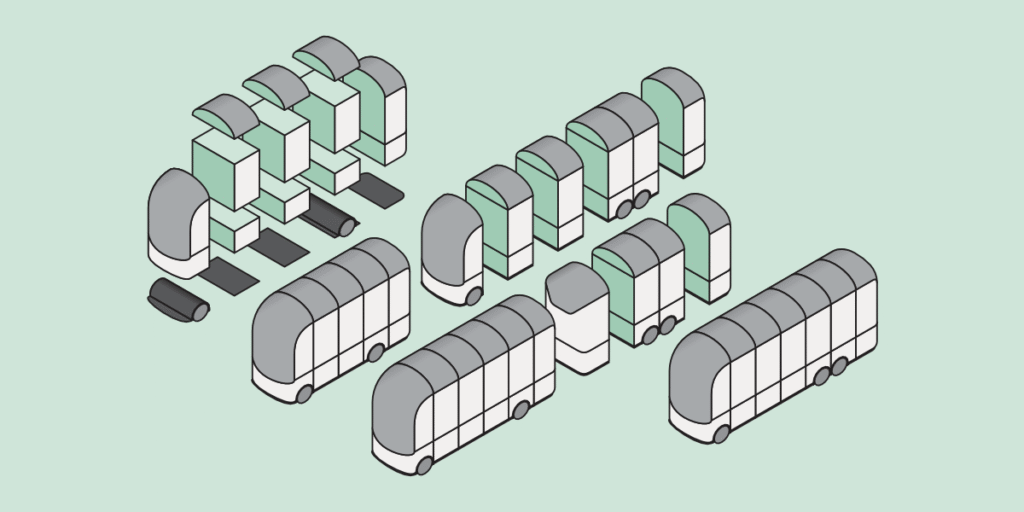

Repetition is often seen as monotony, but in modularity it becomes rhythm. When a single unit repeats, it creates patterns that feel both structured and infinite. Rows of kiosks can transform into a marketplace, identical containers can stack into global trade networks, and uniform panels can give rise to flexible architecture. In modular design, repetition is not the end of creativity but the foundation that makes variation possible.

Historical Roots of Modularity

The idea of modularity is older than it seems. Ancient builders already relied on standardized parts: Roman aqueducts were assembled from repeating arches, and Japanese temples used wooden joints that could be rebuilt and replaced without nails. Even the humble clay brick is a perfect example, a small, uniform unit that can be stacked and repeated to create walls, houses, and entire cities.

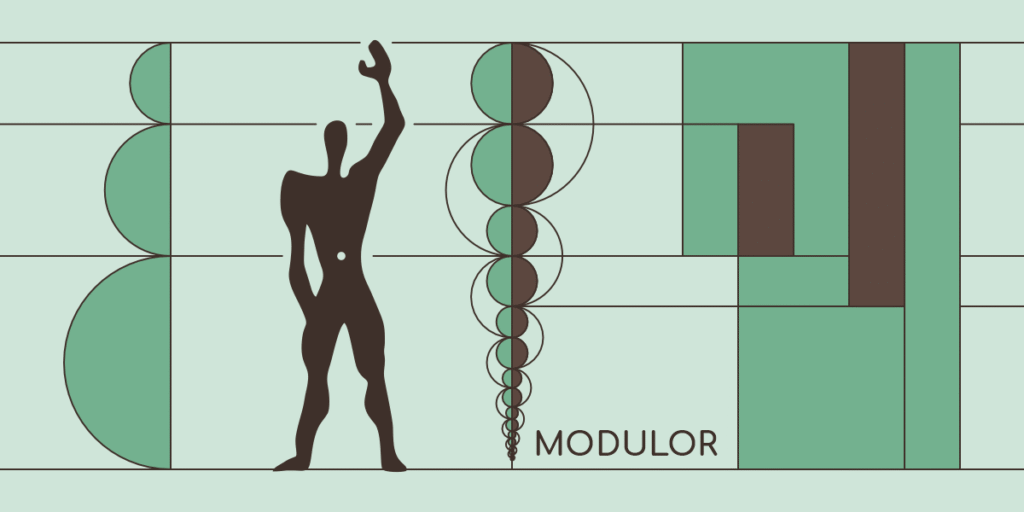

Centuries later, the Bauhaus movement embraced the same spirit, reducing forms to essential shapes and searching for systems that could be scaled and repeated. In the mid-20th century, Le Corbusier proposed the Modulor, a measuring system based on the proportions of the human body. It was an attempt to bring order and harmony to design through repetition and scale. Later, Saša Mächtig’s K67 kiosks turned city streets into modular landscapes, with prefabricated units that could be joined, rearranged, or moved as urban needs evolved.

In the second half of the twentieth century, another form of modularity transformed the world in a different way. The invention of the ISO shipping container standardized global trade, creating a system where identical steel boxes could move seamlessly between ships, trains, and trucks. This simple modular unit reshaped economies and made the modern logistics network possible.

Each example shows the same principle at work: simple parts, endless possibilities.

Why Modularity Matters Today

Modularity shapes how designers think and create. By working with defined parts, designers can balance consistency with innovation, allowing products and systems to feel both familiar and fresh. It is why a smartphone feels intuitive to use and why a building system can expand without losing its identity.

The economic impact is equally important. Modular production reduces costs by standardizing components while still offering variety. A single part can be mass-produced yet serve in countless configurations, making products more affordable and accessible. It is the reason a company like IKEA can offer global furniture solutions, and why modular construction is increasingly favored in housing and infrastructure.

Sustainability is another key factor. Modularity enables repair, replacement, and reuse instead of waste. Instead of discarding an entire product, individual parts can be swapped or upgraded, extending lifespans and reducing environmental impact. This principle applies as much to architecture as it does to technology, making modularity a natural ally of circular design.

On a personal level, modularity empowers choice and adaptability. It respects that one size does not fit all, allowing individuals to tailor solutions to their needs. A modular office system can expand with a growing business, a modular home can adjust to a family’s changing life, and even software today is modular, adapting to different users.

Finally, modularity thrives in cross-platform connections. A system designed in one field often finds applications in another. The same container that carries goods can become a building block for temporary housing, and the same modular logic behind toys can inspire advanced engineering. Modularity is not confined to a single discipline, it is a universal design language that connects them all.

Modularity as a Way of Thinking

Modularity is not only about the final product, it also transforms the way things are made. By breaking a system into smaller elements, each part can be designed, tested, and improved on its own before becoming part of the whole. This way of working makes projects easier to manage, supports teamwork, and allows progress to happen step by step.

To succeed, modular design must also be timeless and neutral in style. Because it operates on many levels such as structure, function, and appearance, it cannot rely on passing trends. True modularity is durable, flexible, and open to reinterpretation across decades. This is why a brick wall, a shipping container, or a modular kiosk can feel both familiar and endlessly adaptable.

This way of thinking has even shaped the digital world. Modern computer systems are built on the same idea, with programming organized into modules and functions. Developers reuse and connect components much like designers assemble bricks or architects link prefabricated units. It is a shared logic of adaptability that moves from the physical world into the digital one.

It is also important to note that good modularity does not mean endless mass production. Instead, it offers a framework for creating fewer but better components that last longer, adapt further, and waste less. Modularity, when done right, is not about producing more things but about making things that can live longer and grow with us.

A Modular Future

Modularity has always been more than a design method. It is a way of thinking that adapts to changing times and connects disciplines from architecture to technology. It shapes how we build our homes, how we transport goods, how we use our tools, and even how we write code. In a world that demands both resilience and creativity, modularity offers a framework that is flexible, sustainable, and deeply human.

As we look to the future, modularity will continue to guide new approaches to living and moving. It invites us to imagine systems that can grow, shift, and respond to our needs while keeping harmony and order at their core. It is within this vision that projects like Domovago find their place, drawing on history and reinterpreting it for tomorrow.

Key Takeaways

- Modularity is timeless: from clay bricks to digital code, breaking systems into adaptable parts creates order, flexibility, and resilience.

- Good modularity means better living: durable, flexible components allow creativity, sustainability, and personal choice without fueling mass consumption.

- Domovago continues this vision: reinterpreting modularity for future living, where homes and vehicles can grow and adapt with us.

Credits

- Written by: DB

- Images: DB, Freepik, Lego bricks by Sunfox