Imagine a morning in the 1980s. On your way to work you stop by the kiosk where a small line has already formed. Brief words are exchanged, the line moves quickly, and soon it is your turn. You buy a newspaper and a pack of cigarettes. The smell of fresh ink on paper mixes with tobacco, the seller offers a warm “have a nice day”, and off you go. A small ritual repeated by thousands every day, made possible by a simple booth on the corner.

First Step Inside a K67

Seeing a kiosk in action was nothing unusual for me. I grew up in Yugoslavia, where almost every street corner had one. In my small hometown they mostly served as newspaper stands or ticket booths with an employee inside and a customer outside. You never really saw much beyond the small window, which created a sense of mystery about what it looked like inside. I remember them painted mostly in red or white.

But when traveling with my dad to Ljubljana, the capital, we could find larger configurations, sometimes in other colors, with more windows and a bigger presence. On one visit he took me to a fast food kiosk, one of the larger red units with windows on almost every side.

I remember stepping from a brick that served as a step, through the glass doors, onto a black vinyl floor patterned with circles. To me it felt like entering a spaceship. You passed from one chamber to the next until reaching the counter where they sold burgers, hot dogs and other, more local, fast food. I do not recall eating a hot dog before that day, so in my mind it was futuristic food in a futuristic looking place.

Along the windows ran tall bar tables with stools facing outward. We sat there, eating and watching the flow of people outside. It felt cozy, modern and alive.

The Vision Behind the Kiosk

Today I can imagine how Saša Mächtig envisioned the kiosk when he made his first sketches, how something as small as a booth on the corner could shape public life through good design. What felt to me like a spaceship was in fact the result of a clear idea, to bring modular and functional architecture into everyday life.

Saša Mächtig was born in Ljubljana in 1941 and studied architecture at the University of Ljubljana under the mentorship of Edvard Ravnikar, who is often considered the second most important Slovenian architect after Jože Plečnik. Under Ravnikar’s wing Mächtig absorbed a sensitivity for how architecture and design could shape public space and everyday life.

Throughout his career he dedicated much of his energy to education. He taught product design at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana, where generations of students learned from his ideas about functionality, modularity, and social responsibility in design. He was also active in international academic circles and design organizations, contributing to discussions about how design can serve society.

His personal motto is “With imagination and will, everything is possible.” This reflects his belief that design is not only about creating objects but about enabling change. For Mächtig, design is a tool to transform everyday environments, to respond to social needs, and to open possibilities for a better future.

Read about other Saša Mächtig products in our article on 5 Saša Mächtig Modular Designs.

A Modular Booth for Everyday Life

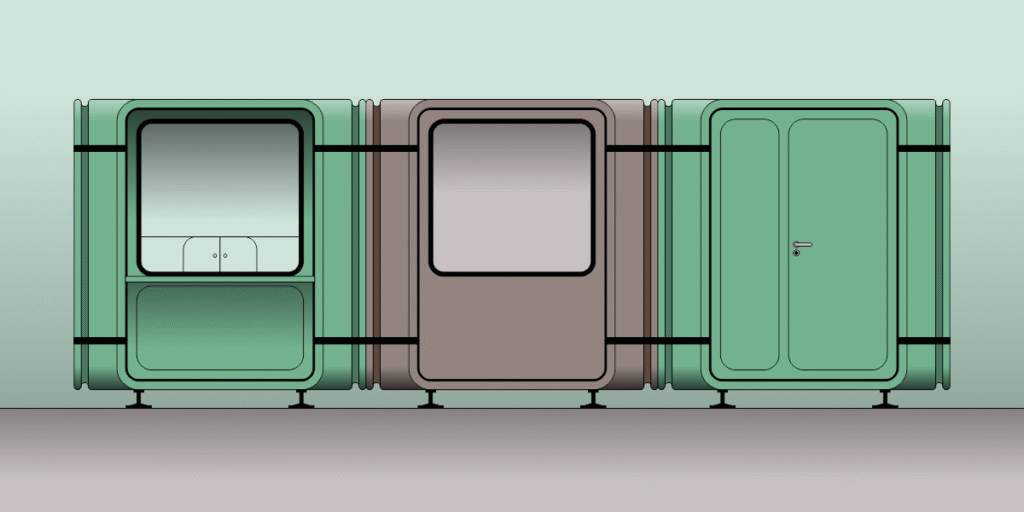

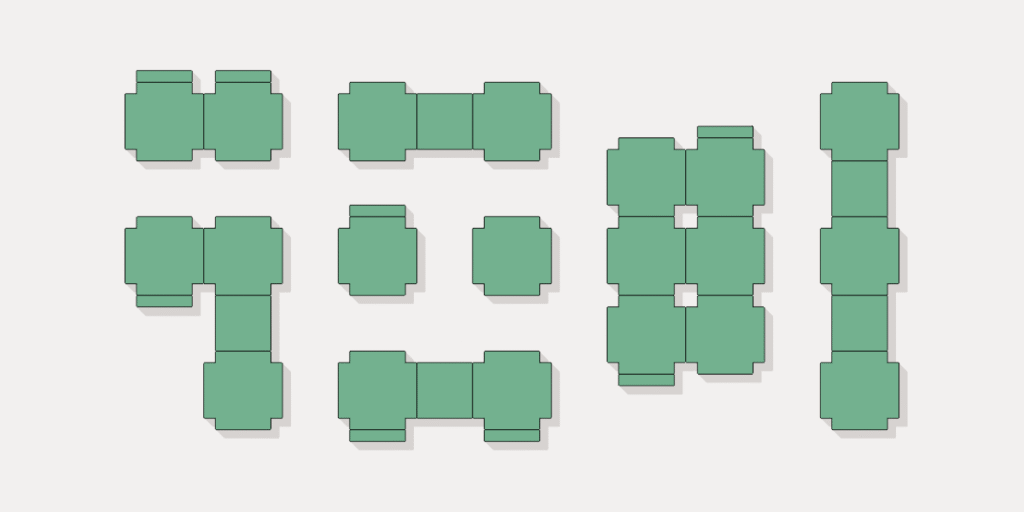

The K67 kiosk was designed in 1966 and put into production the following year. From the start it was conceived not as a single object but as a system. Each unit was based on fiberglass reinforced polyester modules that could be produced in series and assembled in different ways. A kiosk could be as small as a single booth or extended into larger configurations with additional modules, windows, and doors.

The structure was simple and clever. The self-supporting shell meant that walls could be opened with generous windows, creating visibility and a sense of transparency. Rounded edges softened its modernist lines, while bright colors gave it a friendly, approachable character. It was architecture on a small scale, yet it carried the same ambitions of flexibility and functionality found in much larger projects of the time.

Production began in Slovenia and quickly spread across Yugoslavia. Thousands were made and exported to countries across Europe and beyond. On street corners they became newspaper and tobacco stands, flower shops, ticket booths, and fast food stalls, and at sporting events they even served as commentator booths.

The K67 was never meant to dominate the city. Instead it offered a modest, practical presence, shaping the rhythm of public life in ways that often went unnoticed. For many people it was simply part of the urban landscape, but in reality it was one of the most successful examples of modular industrial design in the region.

Even with its simple appearance the kiosk carried a sense of familiarity. You could find it in your small hometown and then see the same form again when visiting a big city. That continuity softened the cultural distance between the two. In a way the kiosk brought a piece of the city into smaller towns and carried a touch of small town life back into the city. It created a shared language of public space that felt both practical and strangely homelike.

Legacy and Influence

By the 1990s the production of K67 kiosks slowed down and eventually stopped. Many units were removed or replaced as cities modernized, yet the kiosk never truly disappeared. Some were preserved in museums and design collections, recognized as symbols of Yugoslav modernism and examples of how industrial design can shape daily life. Others survived on the streets, weathered but still in use, carrying their history into the present.

Designers and architects often point to the K67 as proof that small scale interventions can have a large impact. It showed how modularity could serve public needs with efficiency and character, blending practicality with identity. The kiosk became more than a selling point, it was a meeting point, a landmark, and a reminder that design can quietly transform the way people live in cities.

For Domovago this legacy is a source of inspiration. Just as the kiosk offered flexibility, adaptability, and a sense of place in the public realm, the Domovago project seeks to carry those same principles into the scale of a mobile home. The idea is the same at heart, to use modular design to create spaces that feel human, accessible, and alive.