Sixty years after his passing, Le Corbusier’s legacy continues to shape the way we think about homes, cities, and even mobile living spaces. Guided by his belief in human scale, functionality, and the Modulor system, he created works that go beyond style and fashion. From architecture to furniture, his creations remain as relevant today as they were in his time. In celebration of his enduring influence, here are five timeless Le Corbusier works that redefined what it means to design for life.

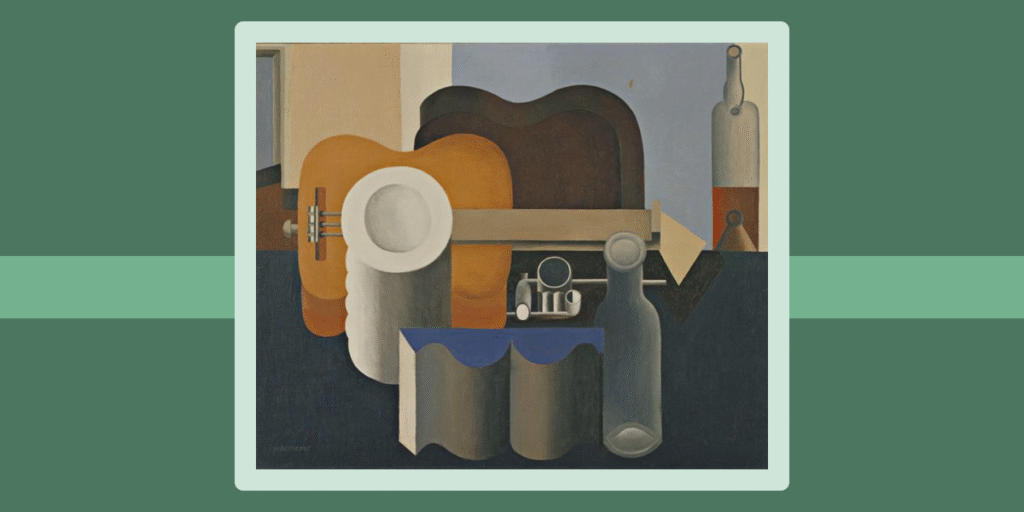

1 Still Life (1920)

Before he became a world-renowned architect, Le Corbusier explored the language of form through painting. His “Still Life” (1920) belongs to his Purist period, where he stripped Cubism down to its essentials. The painting reduces bottles, instruments, and everyday objects into clear geometric shapes, creating harmony between art and proportion.

This work shows how Le Corbusier sought unity between the visual arts and architecture. The same sense of order, balance, and human scale that guided his canvases would later appear in his buildings and furniture.

2 LC4 Chaise Longue (1928)

Nicknamed the “relaxing machine,” the LC4 Chaise Longue captures Le Corbusier’s belief that furniture should adapt to the human body, not the other way around. Designed in collaboration with Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret, it combines a tubular steel frame with a reclining seat that shifts position with ease.

Unlike decorative furniture of the past, the LC4 is unapologetically functional. Its sleek industrial materials reflect the modern age, while its flowing shape embraces the body in comfort. Nearly a century later, the LC4 is still in production, proving that true design is timeless.

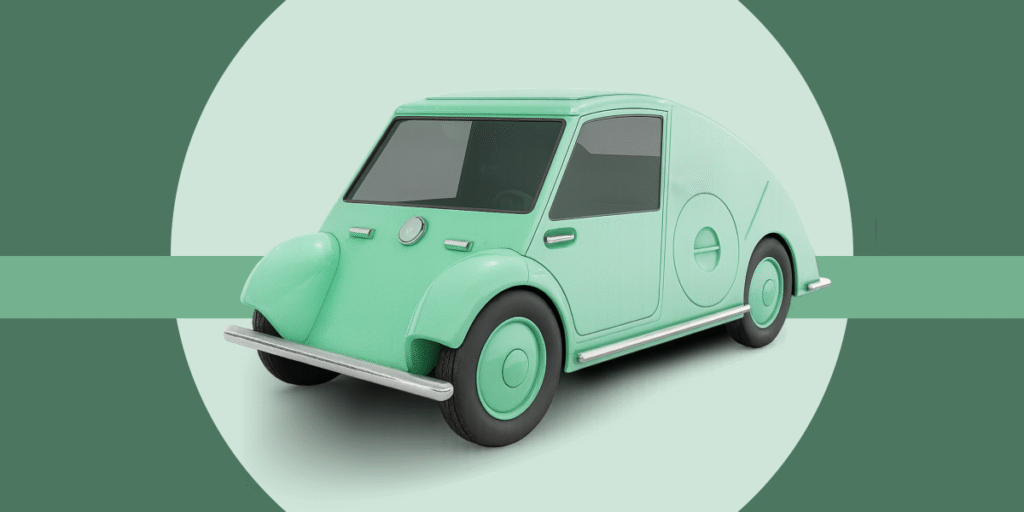

3 Voiture Minimum (1936)

In 1936, Le Corbusier sketched out a radical idea for the future of mobility: the Voiture Minimum. Unlike the big luxury cars of its time, this was a compact, efficient “people’s car” designed to be affordable, lightweight, and practical for everyday life. His vision placed functionality and human needs ahead of prestige, echoing the same philosophy that shaped his buildings.

The Voiture Minimum never went into mass production, but its influence is undeniable. Decades later, the Volkswagen Beetle, the Fiat 500, and even the Citroën 2CV carried forward similar principles of small, accessible cars. Le Corbusier’s vision for a compact, human-centered vehicle feels strikingly ahead of its time, foreshadowing today’s debates about efficiency, urban space, and sustainable transport.

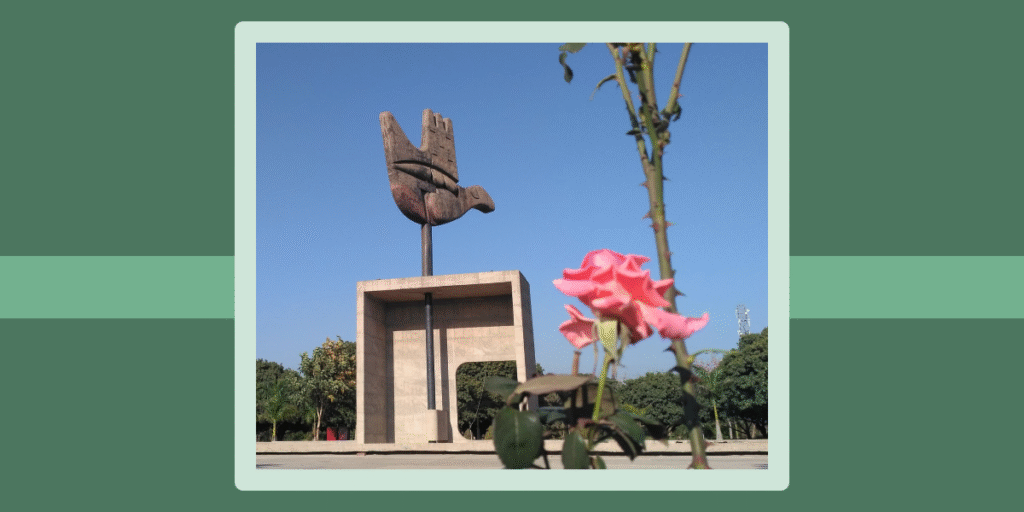

4 The Open Hand Monument (1964)

Among Le Corbusier’s most powerful symbols stands the Open Hand Monument in Chandigarh, India. At 26 meters tall, the metal hand is mounted on a pivot so it can rotate with the wind. For Le Corbusier, the open hand embodied his philosophy: to give and to receive, a universal gesture of peace, reconciliation, and exchange.

Placed at the heart of Chandigarh’s Capitol Complex, the sculpture is not just art but a civic emblem. It represents openness between people, cultures, and ideas, the same spirit that guided Le Corbusier’s urban planning vision. Even today, the Open Hand remains a striking reminder that architecture and design should serve humanity, not just form.

5 Unité d’Habitation, Marseille (1952)

Completed in 1952, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille redefined what housing could be. Le Corbusier imagined a “vertical village” where families could live with dignity and comfort. Inside the massive concrete structure are not only apartments, but also shops, communal areas, and even a rooftop terrace, all designed to serve daily human needs within one cohesive space.

The building was guided by the Modulor, ensuring that every element related to the proportions of the human body. More than just an apartment block, it became a model for modern social housing around the world. The Unité d’Habitation shows that architecture can be bold and monumental, yet still put people first. You can learn about the Modulor in the article Le Corbusier Modulor: The Human Scale.

Credits

- Written by: DB

- Images: DB, Freepik, Still Life / 1920 / Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Open Hand Monument by Anamdas, Unité d’habitation by Ken OHYAMA