A friend once said, "I don't like Bauhaus." It's a sentiment many share, but perhaps the word "like" is the wrong one to use. It is about understanding Bauhaus. It is more than a style in design, art, and architecture. It is a movement representing resistance, unity, and innovation.

The Rise and the Fall: From Weimar to Dessau

Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, in 1919, Bauhaus emerged from the ashes of World War I. It was a revolutionary response to a fractured society and a backlash against the ornate, inaccessible art of the past. The school’s mission was to break down the walls between fine art and craftsmanship, bringing them together under a single roof. Gropius’s manifesto declared, “The ultimate goal of all art is the building!” This statement, often misunderstood as a rejection of historical art, was in fact an argument against its isolation. The movement didn’t want to destroy the past; it wanted to integrate the principles of artistry and craftsmanship into everyday objects and architecture, making good design accessible to everyone.

The school’s most productive and celebrated period came after its move to Dessau in 1925. Under the leadership of Gropius and later Hannes Meyer, the focus shifted towards a more rigorous functionalism. This era saw the production of the iconic furniture, textiles, and architecture that defined the Bauhaus style. The Dessau campus itself, designed by Gropius, was a masterpiece of the movement, a testament to its principles of clean lines, simple geometric forms, and the use of modern materials like glass and steel.

The political climate in Germany ultimately led to the demise of the Bauhaus. The Nazi regime, viewing the school’s progressive, internationalist, and often socialist-leaning ideals as degenerate, forced its closure in 1933. Despite its short 14-year lifespan, the school’s influence had already spread globally. Its teachers and students, fleeing persecution, carried the Bauhaus philosophy with them, establishing new schools and influencing design and architecture around the world. The physical school was gone, but its ideas had become unstoppable.

Philosophy: Design Principles

The Bauhaus movement was a rebellion not just against the aesthetics of the past, but against its very philosophy. The school’s core curriculum was a radical departure from traditional art academies, focusing on multidisciplinary principles designed to create a more harmonious, functional, and efficient world.

The most famous of these principles is “Form follows function.” The Bauhaus masters believed that a design’s aesthetic quality should be determined by its purpose. A chair should be designed primarily for sitting, a teapot for pouring, and a building for living and working. This led to a stark, unadorned aesthetic where every line, curve, and material choice had a logical reason for being there. It wasn’t about decoration; it was about honest, purposeful design.

This emphasis on utility led to a philosophy of Rationalism and Simplicity. Bauhaus sought to strip away the ornamentation and historical references that had defined earlier design movements. The goal was to reveal a design’s fundamental structure, using clean lines, simple geometric forms, and a limited palette of primary colors. This rejection of excess created an aesthetic of clarity and efficiency, a design language that was universal and timeless, unbound by cultural or historical trends.

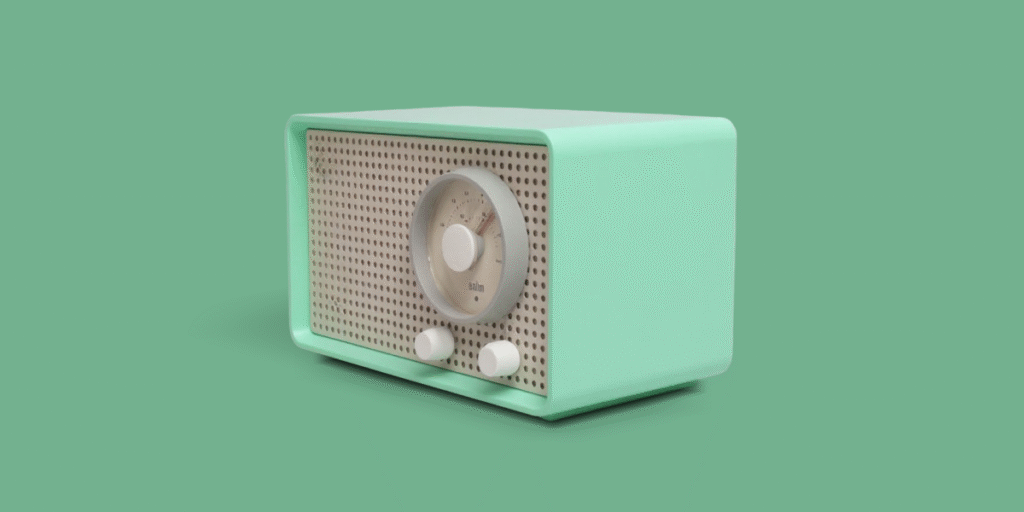

Finally, the movement was a celebration of New Materials and Industrial Production. The Bauhaus school embraced the technological advances of the 20th century. Instead of rejecting industrial tools and materials, they saw them as the means to bring good design to the masses. They were among the first to experiment with tubular steel, glass, and concrete, transforming these materials into elegant, mass-producible objects. This fusion of art and industry was a core tenet of the movement and a key reason for its lasting influence.

These principles didn’t exist in isolation. They connect with other design philosophies that shaped modern thinking, such as Minimalism, Brutalism, and more. Some of these are presented in the article 5 Philosophies for Domovago.

The Lasting Influence

While the Bauhaus school was forcibly closed, its core philosophies proved impossible to contain. The diaspora of its teachers and students, including figures like Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer, carried its principles to new schools. The influence of Bauhaus can be seen everywhere in our modern world, from the clean lines of an Apple product to the minimalist practicality of IKEA furniture. Its focus on simplicity, functionality, and mass production became the foundation of the International Style of architecture and has shaped everything from graphic and industrial design, to urban planning. The idea that form should follow function and that good design should be accessible to all has become a universal language, proving that a powerful philosophy is not bound by a single era.

The Domovago Connection

The legacy of Bauhaus is a direct inspiration for the Domovago project. The goal of designing a resilient, affordable, and self-sustainable mobile living solution is, in many ways, an echo of the Bauhaus mission.

Just as Bauhaus was a rebellious act against the rigid art academies of its time, the Domovago project is a rebellion against traditional housing burdens and an answer to global concerns like housing affordability and climate change. It unifies a diverse community of DIY enthusiasts, makers, and creative professionals, bringing them together to share knowledge and build a collaborative, open-source project. It is a project of innovation, embracing technology and new materials to design a functional, aesthetically pleasing, and self-sufficient mobile home.

The ultimate goal of all art could be the Domovago. And you don’t need to like it. You just need to understand it.

Key Takeaways

- More Than a Style: Bauhaus was a revolutionary philosophy that unified art, craftsmanship, and industry.

- A Timeless Legacy: The principles of Bauhaus, such as “form follows function,” continue to influence modern design.

- The Domovago Inspiration: The project embodies the rebellious and innovative spirit of Bauhaus.

Credits

- Written by: DB

- Images: DB, Freepik, “Das Bauhaus” by Maarten